Reflective practice: Learning through transforming experience

Posted on 4th January 2024 by Elena Oncevska AgerDrawing on the work of Lewin, Dewey and Piaget, Kolb (1984) argued that all learning is essentially experiential in nature, and that new knowledge is a result of a transformation of experience. We cannot therefore talk about learning as a finite thing: knowledge can evolve in light of new experience.

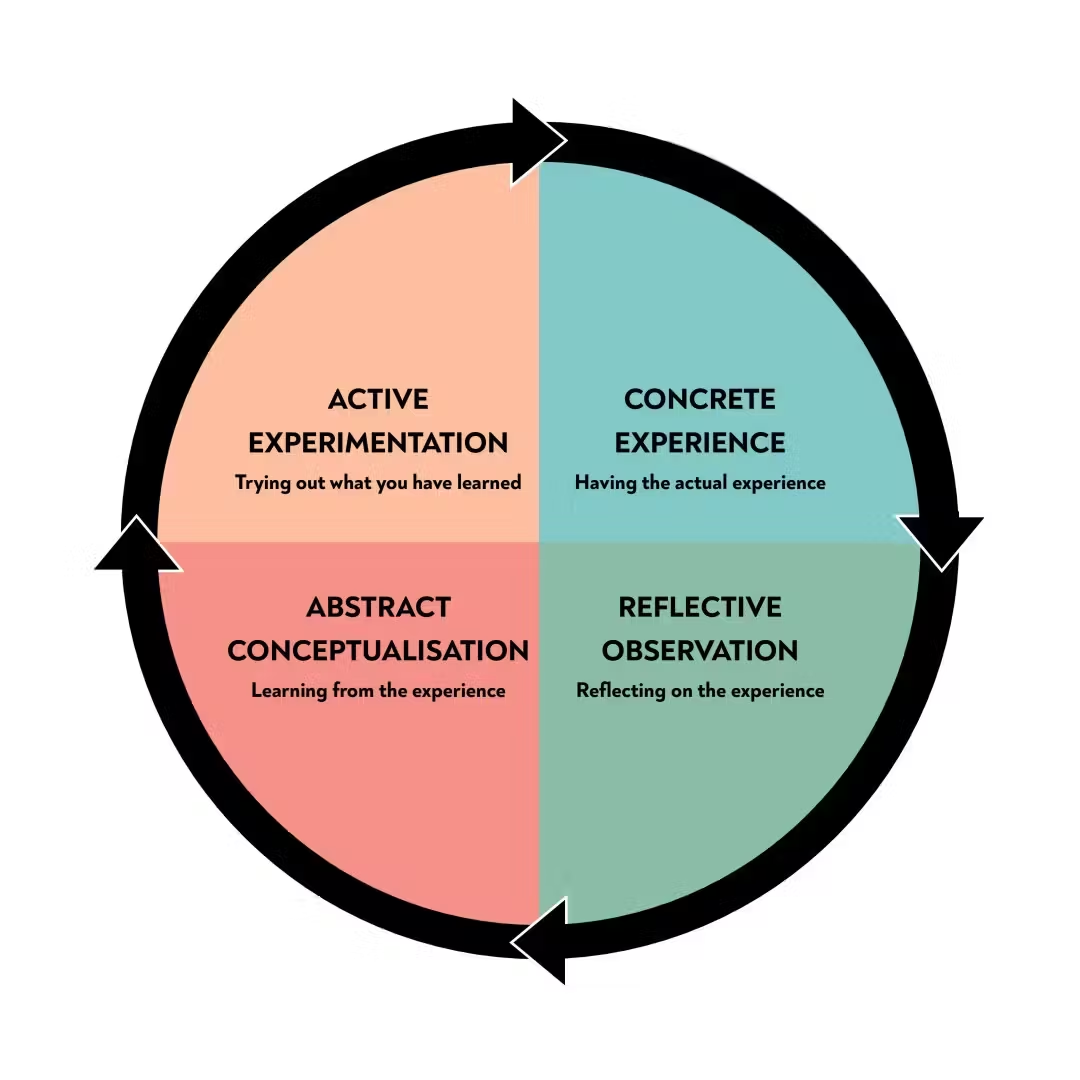

Kolb proposed a reflective model typically referred to as Experiential Learning (see Figure 1). It is composed of four stages:

- description of a concrete experience

- evaluating and understanding the experience

- drafting alternative reactions to similar future experiences using the literature and

- trying out the newly drafted alternative plans of action — an exploration from which new experiences emerge, which can serve as starting points for new reflective cycles.

Figure 1: Kolb’s (1984) Experiential Learning reflection model, taken from

https://www.simplypsychology.org/learning-kolb.html

Systematic Informed Reflective Practice

My experience as a teacher educator using a mentoring approach in my work with EFL pre-service teachers (PSTs) has shown that a mentoring protocol which aligns with the work of Kolb on experiential learning might be a very practical tool to promote reflective practice. A mentoring protocol is used as a framework to guide mentorials, i.e. reflective discussions between mentors and mentees.

The protocol is called Systematic Informed Reflective Practice (SIRP) (Malderez and Wedell, 2007; Malderez, 2015 and, in more detail, Malderez, 2023) and it usefully breaks down the reflective process in five, distinctly outlined steps. Each step is phrased as a question for the mentee to consider while engaging in a post-lesson mentorial with a mentor who only facilitates the process, offering ideas and other support when invited:

- What happened? (The mentee describes in as much detail as possible a moment from the lesson that stood out to them for any reason — this can be an issue, a success or a puzzle they experienced in their teaching.)

- How can I understand this? (The mentee lists as many possible explanations for what was described at Step 1.)

- What else do I know? (The mentee considers what other people have said or written on the topic, as well as anything else they know about the context: learners, class, school).

- What is the most likely explanation? (The mentee goes back to Steps 2 and 3 to arrive at a most likely explanation.)

- So what? (The mentee reflects on what the reflective process means for their learners’ as well as their own learning).

The protocol is designed in such a way as to limit the mentor’s role to a non-judgemental facilitator whose task is to support the mentee to arrive at their own, informed understandings and decisions, thus developing ‘learnacy’ (Claxton, 2004), i.e. the mentee’s ability to manage their own learning. Learnacy is a central skill for practitioners who are looking to continue developing as professionals beyond training and act agentically in their workplaces.

SIRP served as inspiration for the Noticing and the Retrospective Mentorial parts of our reflective cycle.

My experiences of reflective practice

I engage in reflection on a regular basis, this year with a mentor I greatly admire, and I can say that the benefits are many. It is one thing to think about something that stood out for you in the work you do while going about your daily tasks. Such thoughts typically remain messy and with a limited potential to yield anything actionable.

Engaging in a stepped (SIRP) process with my mentor provides structure for my messy thinking, while slowing it right down. SIRP also demands an open mind to consider possibilities which my intuition might otherwise leave little room for. SIRP activates contextual and theoretical knowledge, which I find very helpful in making fuller sense of what I have noticed in the first place, before sketching a plan for alternative action in a future similar scenario. A competent mentor can enrich the process by suggesting lines of thinking that may be unavailable to me. By the end of a SIRP process, and mostly due to its dialogic format, I feel I have arrived at more realisations and plans than I would have otherwise, on my own. The act of sharing my reflection with a mentor I trust makes the experience one of emotional offloading, with therapeutic effects. The result is a feeling of direction, calm and a readiness to notice more and better next time.

Why Noticing?

Aware that competent support for reflection is not always readily available for various reasons (e.g. mentor training, mentor workload) and seeing as the literature provides us with solid reflection protocols, we thought of using AI to help scaffold reflection. This is how Noticing came into being. Noticing is not designed to substitute mentors — we believe that the human touch to any learning is immensely enriching and impossible to substitute. We envisioned Noticing, instead, as a tool to assist a busy mentor with scaffolding reflection, leaving them more time to act in their other roles: to support, model, point mentees to resources/contacts and help them integrate in the target professional culture (Malderez & Bodoczky, 1999).

References:

- Claxton, G. L. (2004). Learning is learnable (and we ought to teach it). In J. Cassell (Ed.), Ten years on: The national commission for education report (pp. 30e35). Brighton: University of Brighton.

- Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Malderez, A. (2015). On mentoring in supporting (English) teacher learning: Where are we now? In D. Hollo, & K. Karoly (Eds.), Inspirations in foreign language teaching: Studies in language pedagogy and applied linguistics in honour of Peter Medgyes (pp. 21-32). Harlow: Pearson Education.

- Malderez, A. (2023). Mentoring teachers: Supporting learning, wellbeing and retention. London: Routhledge, forthcoming.

- Malderez, A., & Bod oczky, C. (1999). Mentor courses: A resource book for trainers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Malderez, A. & Wedell, M. (2007). Teaching teachers: Processes and practices. London: Continuum.

Written by Elena Oncevska Ager

Written by Elena Oncevska Ager

Elena Oncevska Ager is Full Professor in Applied Linguistics at Ss Cyril and Methodius University

in Skopje, North Macedonia.

Her work involves teaching English for Academic Purposes (EAP) and supporting the development of English

language teachers, in face-to-face and online contexts. Her research interests revolve around EAP and

language teacher education, with a focus on mentoring, group dynamics, motivation, learner/teacher

autonomy and wellbeing.

Elena is particularly interested in facilitating reflective practice, in its many forms, including

through using the arts and by using AI to facilitate it. Her investigations are designed in such a way

as to inform her practice of supporting learning and teaching.